THE BLIND LEADER, 2018, performance and installation

Concept and Choreography - Rachel Monosov

Performers

Rachell Bo Clark, Brogaard Camilla, Judith Förster, Maciej Sado (K60 / Berlin)

Rachell Bo Clark, Brogaard Camilla (Kunsthaus Hamburg, Bundeskunsthalle)

Arad Inbar, Sammie Hermans, Paolo Yao, Karolina Krynicka (Art Rotterdam)

Keren kraizer, Thiago Antunes (Art Brussels)

Alexandra Berger, Isaac Owens, Jacob Storer (Catinca Tabacaru Gallery,NY)

The Blind Leader composed largely of models for imposing limitations on the human body.

At the meeting point between object and body, is a forced gesture. The limitation of one’s movements is imposed, and quickly becomes one's nature, without being natural at all. Once conditioned, what actions can one take? Each model creates a scenario that requires wrestling with social construction.

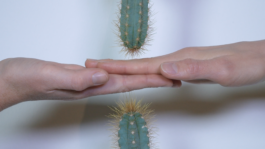

The fingerprint taken at a border has a hint of criminality built into the process of identification. This constant suspicion of the individual is highlighted in my presentation of Fingerprint. Held by the neck and around the knee, the mobility of the body is challenged while an imprint equivalent in uniqueness and wonder to those found in imposing geological formations is taken as a form of intrusion and control. The space; a scenography of a state; a proposal [of a conditional state].

Essay by Mariette Papic

The Blind Leader

The blind leader is never one person, but a group of people who choose one head, while the others are the arms, the legs, ears and nose. The only thing a tyrannical group does not have between them all is sight.

Whether we are safe within the established community, or within a state of dislocation, the prevailing culture can carry with it the requirement that we move slowly and with permission. This is not a normal state of consensus-driven decision making, nor a self-guided state of deliberation. Instead, the closed culture demands permission for every statement, every decision, every movement, to be approved by some leadership. The burden of obtaining this permission is addressed by the artist, Rachel Monosov in her new exhibition, The Blind Leader. In Waiting Room we encounter this burden of permission through the use of fencing. The actors wait for something unknown, separated from the viewer and the rest of the world. The simple fencing of the waiting room could be transgressed physically but the weight of culture makes the actors obedient.

We decided over time, that some people were worth more than others. We gave out gifts for some, from the day of birth, while placing obstacles in the paths of others. We used words like God to give us a reasoning for the disparity, and later we used the word science and most particularly Darwin, to justify our systems. As it becomes clear that we misunderstood nature, that Darwin’s survival of the fittest was only partially correct, it remains our task to update our culture to match reality. This much needed revision to our systems is resisted by many because although it is aligned with the newest technologies, as well as our biology, it is contradictory to the models upon which our cultures are built. The fingerprint taken at a border has a hint of criminality built into the process of identification. This constant suspicion of the individual is highlighted in the artist’s presentation of Fingerprint. Held by the neck and around the knee, the mobility of the body is challenged while an imprint equivalent in uniqueness and wonder to those found in imposing geological formations is taken as a form of intrusion and control. The link between complacency and blind authority will continue to be heightened as we propel into the Information Age and our rapidly evolving technologies. Each of us will stand as newcomer at this threshold between ages, and each of us will, in that sense, bear some imprint of the refugee experience. Even those who do not move across physical borders will be forced into this position of migrant when dealing with the profound changes of culture that must attend such a great period of transformation. The Space In-Between creates a sense of the never ending balancing act that all who cross borders have with the sharp ends of authority. In effect, the constant tension in this work is equivalent to a mental state that is tasked with code switching while it must give away nothing; no sense of effort or labor.

Instead of seeing our leaders as bridges to the greater wisdom we have often allowed them to become unquestionable figures of authority. We have clung to these figureheads whether we agree with them or not, simply because they fulfill a parental role we crave. According to the schools of religion, or their secular counterparts, we have allowed the few to wield great authority over our lives so that we may live in some escapist manner. This desire for authoritarian messiahs or for the safety of homogeneous days that no longer exist has resulted in fences that deny more than individual entry, they deny the power of the human species as whole. These fences that our leaders have erected are meant to act not as membranes between interlinking objectives or communities but as obstacles to cooperation. These fences are meant to keep out newcomers but in effect they serve as unacknowledged pens for all common people. This movement towards separation of humans from one another leads to a constant experience of isolation so profound that even those with eyes are rendered blind. By repeatedly walling ourselves off from nature or from what we actively perceive we have found there is nowhere else to turn our fixation but onto ourselves. Power politics now dominate our lives not exactly as they did when we first gave birth to our present visions of God, or our scientific gods, but they are still tinged by lesser commandments that demand allegiance to ideology and identity before all else. In this present state of transition the systems still move but their collective vision is impaired. The collective head of our power system is cut off from its sensory organs, and together we grasp in the dust for some sense of what is next. To see or not to see, where our power is surrendered and where it can be recovered, this is the question asked repeatedly by Rachel Monosov in The Blind Leader.

We don’t need bloody revolution in most cases.

To engage in a global restoration of power we must be willing to see ourselves as a globe of newcomers. To open our doors to the shifting needs of our biosphere and by engaging it with a philosophy of interconnection. We must rewrite our perceptions of power so what we see is transparently shared. To achieve this transparency we must uncover a new version of society, one where interconnection precedes ideology. By embracing power through projects of interdependence we can do more than exhaust ourselves on resistance. We can see leaders once again as capable servants playing roles no greater or lesser than each of our own. We must move power away from its theatrical tendencies that provide false safety and into a more administrative role that presupposes and encourages a new level of maturity in the human race.